U.S. President Donald Trump, once a critic but now a supporter of TikTok, is granting the app’s China-based parent company, ByteDance, a second 75-day extension to finalize a deal that would transfer ownership of TikTok to an American entity. For Trump, keeping TikTok alive aligns with a campaign promise – especially after it became clear that a wave of young voters were outraged by a congressional law threatening to ban the app unless ByteDance sells it. While the legislation allowed only one extension for a sale, Congress has yet to push back against Trump’s decision to offer another. However, the most important issue is tied to the nature of TikTok and its weaponization in Beijing’s war against the West.

Last April, the U.S. Congress passed a bill forcing social media apps that are “controlled by a foreign adversary” to come under the control of a U.S. or friendly country owner at market price. If the owners did not sell such apps, they could no longer be legally downloaded from app stores. This so-called “TikTok ban” – which is not actually a ban, just a rule for corporate ownership – was set to go into effect the day before Trump’s presidential inauguration.

China fought in the Supreme Court but ultimately lost, and the Biden administration was able to “ban” the app. TikTok’s Chinese parent company, ByteDance, had many months to sell TikTok to a suitable buyer, and would undoubtedly have done so (a high-stakes bidding war involving major players like Amazon, Microsoft, Oracle, and Blackstone was sparked) but instead it refused, planning instead to shut down the app altogether, far exceeding the sanction that the US TikTok “ban” provides.

Meanwhile, as President Donald Trump’s tariff war continues to shake the global economic landscape, few mergers and acquisitions feel as closely linked to his policies and their ripple effects as the battle over TikTok.

We can only speculate what prompted Trump’s U-turn, but winning young voters may be a factor. Another contributor may be Elon Musk, whose business is highly dependent on China, and who lobbied against the “ban”.

The reason ByteDance arguably did not sell the app is because the Chinese authorities did not want to give up control of TikTok, revealing the extent of their control of the app (all Chinese internet and technology companies are compelled by law to comply with government data requests, and this power is not limited by China’s borders or the laws of other countries).

Compliance with this is not subject to court orders or judicial review, as is the case with requests by US or European authorities for data from Facebook or any other similar entity. Thus, the behind-the-scenes influence of a totalitarian party need not even be imagined; the direct flow of data is a clear legal obligation with severe penalties.

The refusal to sell the app also indicates that the Chinese government would rather see TikTok in ruins than see it fall into American hands (indeed, the same government didn’t appear to flinch in 2020 when the US forced a Chinese company to sell the gay dating app Grindr, implying there is far more than business at play).

Meanwhile, ByteDance pretends to have separated its US business from its China business, but we can be pretty sure that this is just a performative cover. More than a dozen current and former TikTok employees operating in the U.S. have said that the ties of TikTok’s Chinese owners to “American” ByteDance go back further than the company presents. Key management and technology departments are run from China, which also has access to all the data, while the technical teams are at least half-staffed in China. However, this is just the tip of the iceberg.

The main reasons for the adoption of the TikTok ban were that it spies on its American users and sends their data to the Chinese Communist Party. A secondary reason was that it is subject to Chinese censorship and propaganda that seeks to induce American users to support the Party’s goals. Spying is the main reason because it is the easiest to prove – after details of it were presented to the US Senate, the vote on the motion was 50-0 in favour of the ‘ban’.

TikTok had to admit that it tracks the physical movements of selected journalists and sends the data to its Chinese parent company, and thereby to the Communist Party and Chinese intelligence services. In addition to physical location, the data TikTok collects can include facial and voice prints, browsing history, text messages, and other vital phone functions – TikTok has in fact systematically circumvented protections from Google and Apple against this app behavior. On top of that, the app’s integrated browser acted like a keylogger – that is, a spy program that recorded every keystroke a user made, which recorded everything, including passwords. The data can then be used to intimidate citizens through its alleged network of illegal police stations abroad.

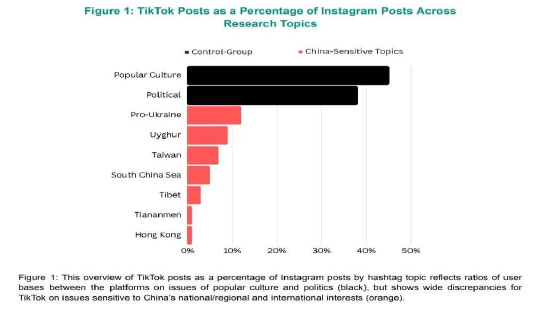

Moreover, the Chinese government potentially could use TikTok to propagandize American youth and to silence those Americans who say things the Chinese government doesn’t like. Researchers at Rutgers University have produced several studies on the subject of information manipulation on TikTok at the request of the Chinese government. The standard methodology is to compare topics on TikTok with similar topics on Instagram and YouTube. The researchers found that the content on these platforms is essentially similar, with the exception of topics sensitive to China. Here’s a chart from one such study that compares hashtags on TikTok and Instagram.

The result shows that content criticising China is much less available on TikTok than on Instagram and YouTube. A follow-up study showed disproportionate engagement with US users who were themselves critically tuned in. This is more important than it might seem, as a growing number of Americans, including a quarter of young people, regularly get their news primarily from TikTok. And because the First Amendment’s protection of free speech in the U.S. Constitution was clearly not intended to protect the right of foreign governments to silence and direct American public debate; ByteDance’s appeal to the Supreme Court over the TikTok “ban” was defeated.

Another reason for banning TikTok is the asymmetry in relations between the West and China over the past fifteen years, especially since Xi Jinping’s rise to power. China has banned Google, Facebook, and a host of other Western apps and platforms, while the West has accepted Chinese media, Chinese apps (and Chinese manufactured goods) as a matter of course. China routinely threatens Western individuals and companies with revocation of market access or other penalties if they and their governments do not toe the Communist Party line on Taiwan, Hong Kong, Xinjiang, etc. However, the West has had no such policy towards China so far, creating a power asymmetry. This is the reason why Chinese apps like TikTok are banned in India for example and generally, it presents a situation that is untenable in an era of strategic rivalry.

To fully understand the situation surrounding the TikTok ban, we need to discuss China’s long-term strategy to usurp the West and replace it with global power primacy. In the 1990s, China hid its ambitions behind a strategy of so-called peaceful rise, in which it intended to gradually accumulate economic power and convert it into military power so as not to provoke a reaction from the West. In turn, Beijing ultimately intends to replace it as the main organizing principle of international relations. To paraphrase Henry Kissinger, empires are not interested in operating within the international system; they aspire to be the international system.

Because China was at the time in a position of weakness in terms of hard military and economic power, its leaders sought to come up with an asymmetric strategy that would attack the identified weaknesses of open Western societies based on the rule of law. The intellectual basis of this strategy is concentrated in a 1999 book by two Chinese colonels entitled Unrestricted Warfare: Two Air Force Senior Colonels on Scenarios for War and the Operational Art in an Era of Globalization. After the US government had it translated into English and released the text to the public, it was published by an anonymous publisher in Panama under the more straightforward title, China’s Master Plan to Destroy America.

Its main theme is how a weaker power like China could defeat a more technologically advanced adversary (i.e. the United States) by various non-military means. The central thesis of the book was that Western thinking about conflict has overwhelmingly focused on technological solutions to open-ended kinetic conflict, ignoring other modes of competition. This was largely true; Western military strategists did not begin to engage more with the concept of hybrid warfare until around 2007, and the debate did not come to the attention of the general public until the Russian annexation of Crimea. The subsequent confusion of this debate and the Western inability to respond flexibly to this challenge arguably culminated in the open Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Such methods of ‘unrestricted warfare’ are various forms of political, informational, and economic warfare, or the use of legal instruments (‘lawfare‘) as leverage over an adversary and to circumvent the need for direct military action.

To quote:

Whether it’s the hacker intrusion [into adversary systems and data exfiltration], a major explosion at the World Trade Center, or the Bin Laden bombing, all of these events far exceed the frequency of bandwidth that the U.S. military understands and is prepared to respond to. The U.S. military is inherently underprepared for this type of enemy in terms of psychology, in terms of retaliation, and especially in terms of the military mindset and the methods of operation derived from it … Degradation [of the power and capability] of an adversary can be achieved in many ways other than direct military confrontation. [These alternative methods] have as much, if not more, destructive power than open warfare, and have already produced serious threats to national security.

Chinese leadership appears to have truly embraced the concept. Indeed, the book explicitly mentions:

For the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) TikTok is a supporting element of its information warfare strategy from the middle of the last decade called the ‘Three Warfares’, of which its components are public opinion, psychological, and legal warfare. This strategy clearly follows directly from the concept of unrestricted war outlined in the book above. It is also crucial to note that the PLA – which is the primary Chinese organ associated with and operationalising the concept of the Three Warfares – is the armed wing of the Chinese Communist Party.

Unlike a conventional national army designed to defend the state and its people, the purpose of the Chinese army is to create a power base for the Communist Party – and, as Mao himself said, to contribute to the revolutionary effort – even beyond China’s borders. Thus, when Western analysts look at the PLA, they generally view it as a state’s and not a party’s army, but this is a purely military view that lacks a clear concept for assessing political warfare and which the authors of the concept of unrestricted warfare intended to use.

The PLA’s control and influence over ByteDance then stems directly from the state policy of “civil-military fusion”, which is another concept introduced under Xi Jinping’s rule, under which the Party takes greater control of the economy, which it then prepares for war deployment according to the Party’s goals.

The overlap of the three war zones doctrine with the operations and techniques observed by TikTok in the United States is perhaps most notable, along with the infrastructure for drone production and shipbuilding, where civilian companies must comply with military requirements so that civilian ships can be easily and quickly used to invade Taiwan.

The use of TikTok in line with the concept of Three Warfares is also openly discussed by Chinese scholars: a 2022 study conducted by the Department of Propaganda and Traditional Warfare at Hunan University states that TikTok’s vast audience, colorful imagery, and rich content are ideally suited for ideological and political “education” of college students and young people. The study argues that TikTok can be used to expand channels for providing “ideological education” to Americans born in the 1990s, a critical demographic group.

This is consistent with the findings of the U.S. Department of Justice, which drafted the TikTok ban, and with other research revealing that the Chinese Communist Party is indeed strategically targeting younger Americans, including college students, among whom it is spreading its propaganda. They are then more likely to support terrorist organizations like Hamas, for example, or to buy into the arguments of the defenders of the world’s anti-democracy league of dictatorships from North Korea to Iran. China’s efforts to use platforms like TikTok to collect sensitive data and manipulate content reflect a broader goal of harnessing the power of new media.

To recap on what we wrote here almost exactly a year ago, with China, this is essentially a faster and more massive use of the techniques the Soviets used with their fake news network in India during the Cold War.

China’s information operations through TikTok do not simply seek to disseminate official propaganda but also include more elaborate and sophisticated long-term programs designed to shape the perceptions and cultural attitudes of Americans, especially American youth, over the long term. Moreover, this program is not only about advanced propaganda but is also halfway between the media war and the drug war. The party apologists would never allow TikTok to operate with such an intensity of trivial content in China, while in America the content being promoted is the digital equivalent of taking drugs in its effect on brain chemistry, which aims to weaken the intellectual capacity of future generations.

TikTok is China’s best, but far from only, information warfare tool. Beijing has flooded American social media with bots and accounts controlled by employees of state-run troll farms seeking to spread misinformation and divisive messages. Over the past 24 months, the campaign has shifted from pushing mostly pro-China content (or classic propaganda) to more aggressively targeting U.S. policy. The campaign used millions of accounts on dozens of online platforms, from X and YouTube to more marginal platforms like Gab, where the campaign sought to push pro-Chinese content. It was also among the first to use cutting-edge techniques such as AI-generated profile pictures.

China’s efforts in this regard have so far been clumsy, fragmented, and, apart from TikTok, mostly ineffective. But the Chinese may eventually learn what works and what doesn’t; after all, the Communist government has gone from the Great Leap Forward and famines to global dominance in many industries.

China, meanwhile, is stepping up cooperation with Russia on information warfare in response to the lack of effectiveness of its campaigns – Putin and Xi have agreed to coordinate their intelligence agencies more closely. Russia may not have China’s economic resources, but it has been at this game for decades, de facto invented its modern form, and understands the divisions in American society much better.

In light of the above, it should be clear to everyone that the Chinese Communist Party and the People’s Liberation Army consider TikTok as one of the several strategic tools for political influence operations and military support actions. TikTok is an instrument of “unrestricted war” against America and the West in general.

There is a massive coordinated effort underway in Beijing to weaken and compromise the US and its global position, involving not only the Chinese government, security services, and military, but also major Chinese companies that are effectively controlled by the Communist Party. Each of these activities is directed towards the same goal – to ensure that the West is no longer able to confront Chinese power. We are currently seeing what it looks like when a would-be-empire without a democratic check on the power of its leadership decides that the West is no longer able to counter its power in Russia’s war on Ukraine. Except that most of the world’s trade actually passes through the Taiwan Strait, not through eastern Ukraine.